The Minister for Health, Andrew Little, made a startling admission “So, what I’m saying is how can we possibly have pumped in billions of extra dollars, and it not appear to have made a difference?”

Conceptualising suicide prevention

Said Shahtahmasebi1 & Russell Gregory-Allen2

1The Good Life Research Centre Trust, New Zealand; 2School of Economics and Finance, Albany Massey University, New Zealand.

Correspondance: Said Shahtahmasebi, email: radisolevoo@gmail.com

Received: 20/8/2023; Revised: 25/11/2023; Accepted: 4/12/2023

Key words: suicide, forecasting, ARIMA.

[citation: Shahtahmasebi, Said & Gregory-Allen, Russell (2023). Conceptualising suicide prevention. DHH, 10(1):https://journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=2966].

Abstract

For decades, in New Zealand and across the globe, suicide prevention policies and strategies have stagnated with more of the same psychiatric intervention. In this paper we report the first round analysis of a series of multivariate trend analysis using forecasting methods. We focus only on the question: what will the suicide rates be in ten years if we continue with the current suicide prevention approach? In New Zealand, official suicide numbers and rates are available for the period 1948-2018. Various time series were plotted and an Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) was fitted to the data. Results suggest that if we continue as we have done with a mental illness approach to suicide prevention then suicide rates will continue to follow an upward trend. And since the mental illness approach has been the only strategy then it can be assumed that there is a very weak or lack of relationship between mental illness and suicide. A change in approach is long overdue.

Keywords: Suicide, time series, forecasting, cyclic

Introduction

Suicide prevention policy development suffers heavily from the Illusory Truth effect, i.e. repeating a claim often enough will make it more believable whether it is true or not. Over the last century, “experts” and policy makers have repeatedly associated mental illness and depression as the root causes of suicide without any supporting evidence (Hjelmeland, et al. 2012). So, every year more funding is directed towards mental health services to provide more psychological/psychiatric interventions. Notwithstanding the unsustainable increases in funding, suicides rates follow an upward trend. Such results have rendered suicide prevention policies useless, thus, creating a “more of the same” strategy with a lack of nuance research.

In 2018, an inquiry into mental health (Mental Health and Addiction Inquiry, 2018) recommended the strengthening of mental health services to achieve a target of 20% reduction in suicide rates by 2030: –

“Prevent suicide. Urgently complete and implement a national suicide prevention strategy, with a target of a 20% reduction in suicide rates by 2030. New Zealand’s persistently high suicide rates were one of the catalysts for this Inquiry. Suicide affects people of all ages and from all walks of life, with thousands of New Zealanders touched by suicide every year. Suicide prevention has suffered from a lack of coordination and resources. Reducing suicide rates should be a cross-party and cross-sectoral national priority. Suicide prevention requires increased resources and leadership from a suicide prevention office. Suicide bereaved families and whānau, who are at increased risk of suicide, need more support, and the processes for investigation of deaths by suicide, which are often slow, traumatic and costly, need to be reviewed.”

To set health outcome targets and to achieve them are two different things. Setting outcome targets strongly implies that the dynamics of health processes are well understood, and parameters are known. We do not understand suicide, per se, and the reasons for an individual’s decision to end their life are at best assumptions and do not explain suicide. Nevertheless, for over a century the idea that suicide is the result of a mental illness has been prescribed as the only official method of preventing or reducing suicide. This is despite the psychiatric model being challenged and discredited e.g. (Hjelmeland et al., 2012; Pridmore, 2014; Shahtahmasebi, 2003, 2005), and the fact that suicide rates continue to maintain an upward trend.

Continual promotion of false beliefs that depression/mental illness are causes of suicide adversely affects the development of policy action strategies, making them inappropriate and irrelevant. For example, the 2006 suicide prevention policy (Associate Minister for Health, 2006), despite its multi-disciplinary narrative, prioritised depression, and suicide prevention budget was dedicated to setting up a web page providing resources and advice to tackle depression (Shahtahmasebi & Shahtahmasebi, 2010).

Furthermore, in New Zealand, antidepressant prescriptions have doubled between 1997 and 2005 (Antidepressant use in New Zealand doubles, 2012), and doubled again between 2005 and 2012 (Ministry of Health, 2007) and have been increasing ever since.

The New Zealand Government’s suicide prevention strategy was tested when in 2019 suicide numbers reached a record high in five consecutive years since 2015. In 2019, the government came up with the slogans “every life matters” and “wellbeing” budget and promised an inquiry into suicide and allocated $1.9 to mental health services, out of which $40 million was to be spent on suicide prevention (Shahtahmasebi, 2019). Typically, the government equates more funds to improvements in services thus failing to monitor budget expenditure. The Minister for Health, Andrew Little, made a startling admission “So, what I’m saying is how can we possibly have pumped in billions of extra dollars, and it not appear to have made a difference?” (Shahtahmasebi, 2022).

The government’s suicide prevention strategy, “every life matters” (Ministry of Health. 2019), like its predecessors adopts a change in language but its action plan focuses on putting a new gloss on the redistribution of mental health services. Thus, there is no change in the approach to suicide prevention.

In summary, the approach to suicide prevention has, in the main, been constant, and is highly likely to remain unchanged. Secondly, suicide prevention policies may well be the biggest risk to suicide. Therefore, in this paper, we apply a forecasting method to explore what the expected suicide rates and suicide numbers will be like in ten years by 2028 in relation to the proposed target of 20% reduction in suicides.

Methods

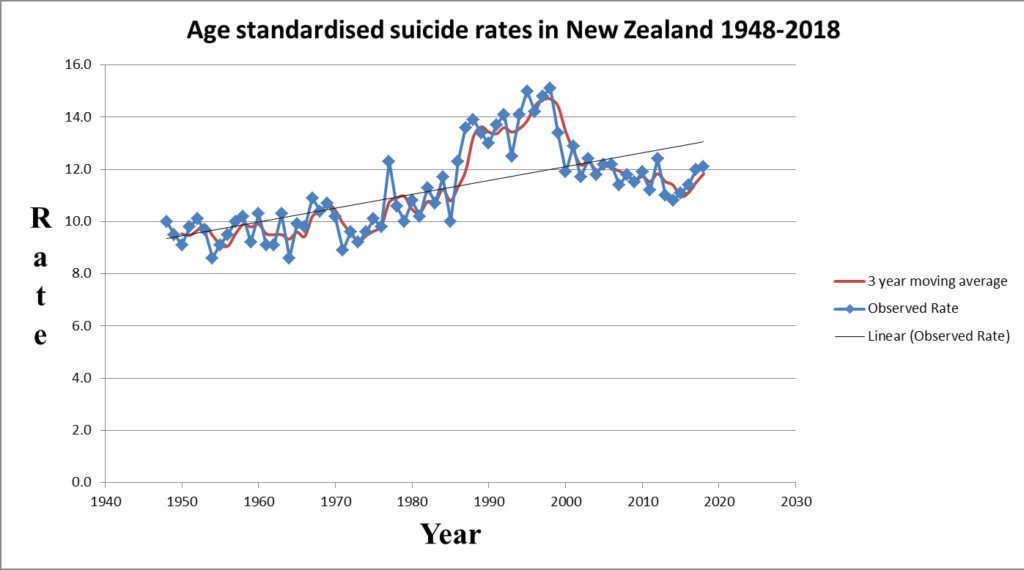

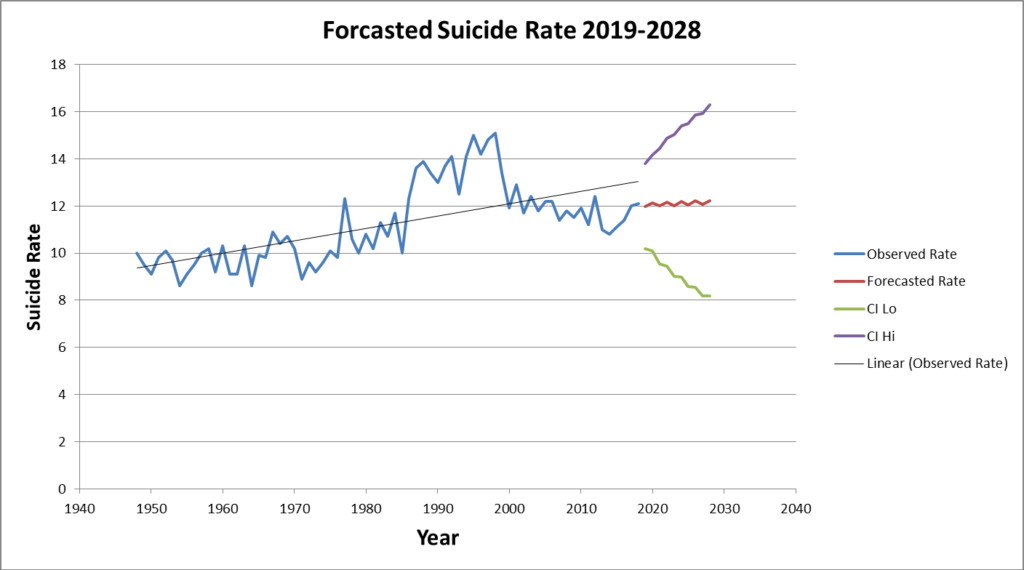

We used an ARIMA process (p=q=1) to forecast suicide rates in New Zealand. We have suicide data from New Zealand Health ministry (https://tewhatuora.shinyapps.io/suicide-web-tool/) from 1948 to 2018. Initially we used 1948-2018 as the estimation period (see Fig 1). As it is well known that the forecasts are very sensitive to the estimation period, we then used as the estimation period 1948 to 2008, forecasting out to 2018. This also allows us to compare forecast vs. actual during 2009-2018. Finally, we extend that process, using an estimation period 1948-2018, forecasting to 2027 (Fig 3).

The first trend analysis will provide some insight about suicide patterns in New Zealand over the last six decades or so. The second analysis provides an opportunity to compare predicted suicide trends against real observations, and the third analysis allows us to explore suicides patterns for the next ten years if we do nothing and continue with the current suicide prevention approach.

Results

The overall suicide rates for the period 1948-2018 is presented in Figure 1. The main features of Figure 1 are firstly, an upward trend as shown by the trend line, secondly, irregular cycles of varying length within much larger cycles better demonstrated by the 3-year moving average line. Patterns in time series are indicative that the time series has a memory and repeats itself. The fact that such patterns continue to be repeated strongly suggests the mental illness approach to prevent suicide has not worked and have become part of the suicide prevention problem.

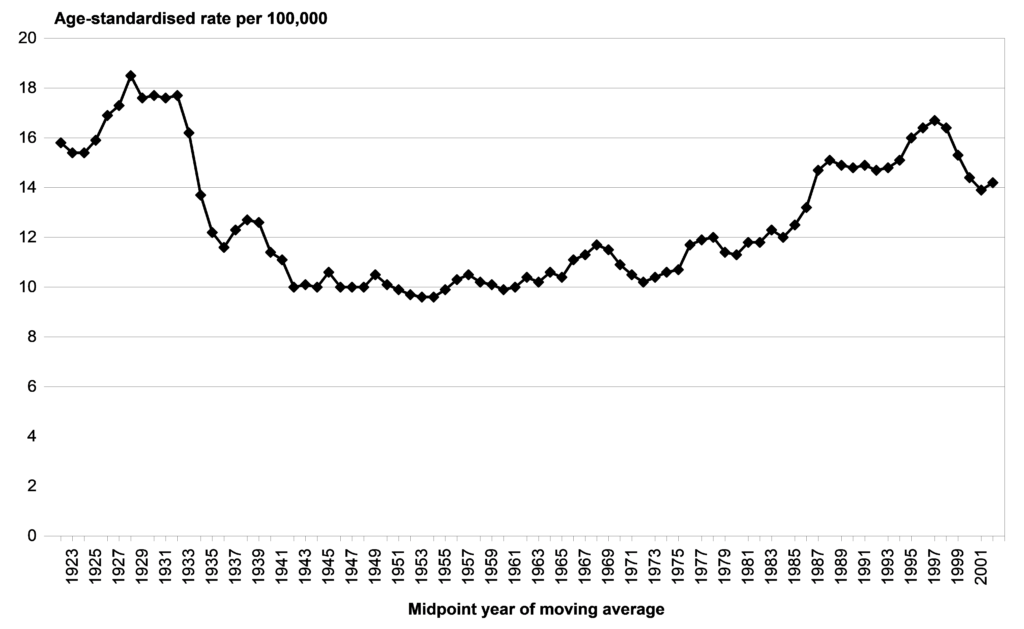

Unfortunately, pre 1948 suicide data was not available for this paper. However, comparing Figure 1 with Figure 1b showing suicide rates for the period 1923-2001 (Ministry of Health, 2006) provides some ideas as to the direction of future suicide trend. For example, firstly, we are able to visualise the outlines of the cycles of 50-60 years. Secondly, the trend for the period 1990-2018 appears to follow closely the period 1923-1950 (cycle downturn).

Figure 1

Figure 1b

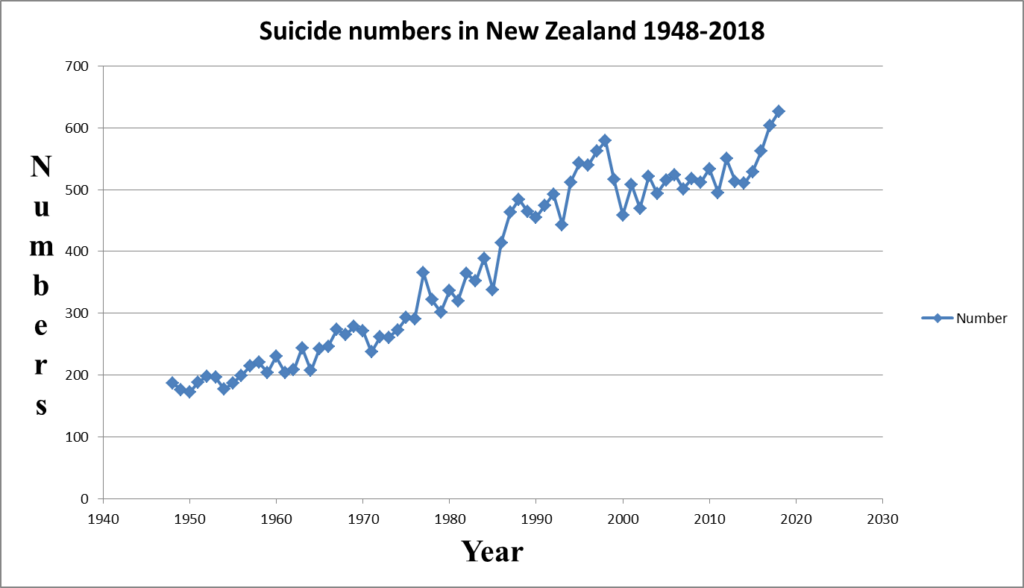

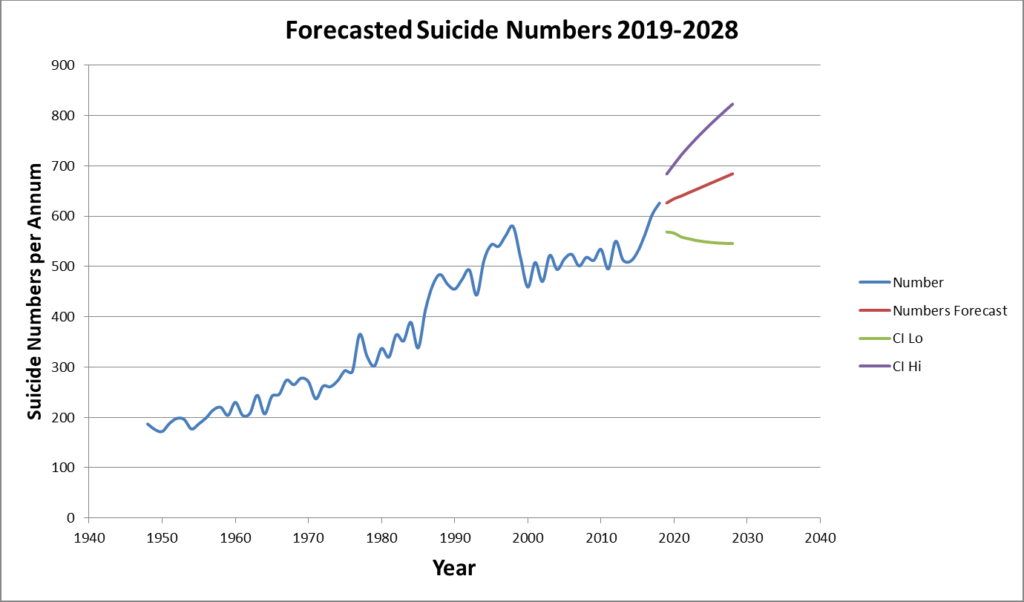

Suicide is preventable and may not be population based as in biologically caused illnesses. for example, as shown in Figure 1 and 1.b, suicide goes up and down while the population of New Zealand has consistently increased year upon year, and continues to do so. Furthermore, suicide is the outcome of a personal decision (for whatever reason) which has a long term and profound impact on family and friends. For these reasons we also provide suicide numbers as shown in Figure 2. It can be seen that suicide numbers have consistently been going up.

Figure 2

A comparison of actual rates with forecasted rate for the period 2009-2018, where actual rates are available, shows that the prediction is in line with the observed values, predicting a similar trend as the observed one. There is no statistical difference between the observed and predicted values (p>0.36).

Figures 3 and 4, show the results for the forecasting period 2019-2028. The main feature of Figures 3 and 4 is that suicides are likely to continue to follow an increasing trend. The forecasts suggest that suicide rates may oscillate around 12 (per 100,000) and an upward suicide rate may be expected. The forecast for the number of suicides is somewhat clearer, suggesting that we can expect to observe more suicide over the next ten years.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Discussion

The results strongly suggest that suicide rates will continue an upward trend if there are no changes in our approach to suicide prevention. Furthermore, until we have succeeded to break or cancel the pattern in suicide trends, we can expect periods of upturns and downturns to be repeated.

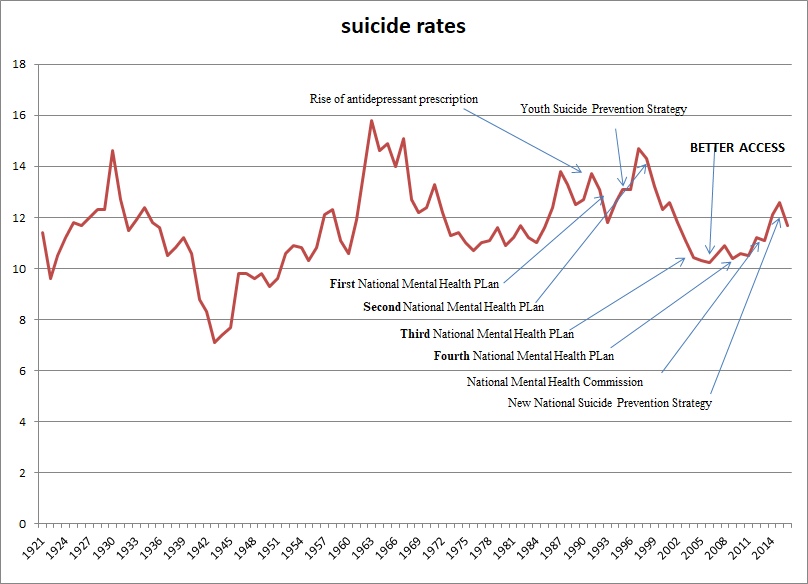

Clearly, there have not been commensurate reductions in suicides due to increased funding. No sustained change in suicides means that it is highly likely that there is little or no relationship between mental illness intervention and suicide prevention. This phenomenon can also be observed in Australian data (Figure 5). No matter how much mental health services are strengthened suicide patterns of upturns and downturns with an upward trend line will persist, which renders useless the claim that suicide is a mental illness (also see (Hjelmeland et al., 2012)).

Figure 5 – Australian long-term suicide rates and prevention initiatives (sources: Australian Bureau of Statistics, (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2004a, 2004b; Jorm, 2018)).

An artefact of a single-mindedness approach to suicide prevention has been the medicalisation of life experiences, lived experiences and behaviour in order to justify a medical approach (Pridmore & Rostami, 2020). The suicide narrative and discourse is restricted to an adverse event causing suicide, e.g. individuals have suicidal intentions or may suicide as a result of, e.g., betrayal by a spouse, bereavement, or loss of fortune. Firstly, people with an adverse life experience might suicide but so do those who have a normal life. Secondly, this strategy forces intervention only when suicidal behaviour manifests and only if individuals request it. Thus, the current approach is based on an Illusory Truth effect where all suicides are forced to fit the mental illness narrative, even where there is no evidence of mental illness.

For instance, during a coroner’s inquiry into the suicide of an adolescent the family GP commented: “I am desperately sad we had no insight into his mental health problems and so were not able to prevent this tragedy.” Why would the GP automatically assume ‘mental health problems’ about a case who was reported to have been a happy and popular person with no sign of any health problems and no evidence of mental ill-health (Shahtahmasebi, 2005)?

The wisdom of the mental illness strategy is that for prevention to be operationalised a mental illness or suicidality must manifest. There are several problems with this ethos. If suicidality is presented then it is too late to prevent, and it is time to intervene. On average between one-quarter and one-third of suicide cases sought and received psychiatric intervention and yet went ahead and completed suicide (Hamdi, et al., 2008; Shahtahmasebi, 2003). This begs the question of how appropriate and relevant are psychiatric interventions and why do they fail to stop suicides in this group?

Clearly, the results suggest that we do not understand suicide, yet, policy makers persist in the belief that suicide is an illness of the mind. As a result, resources have been directed to the medicalisation of suicide.

Conclusion

The results strongly suggest that there has been little or no effect on lowering suicides with the strengthening of mental health services, i.e. based on current available evidence there is no relationship between mental illness intervention strategies and suicides. Furthermore, there will not be a sustained reduction in suicides in the future should we continue with decades of psychiatric intervention policies. To affect a reduction in suicide rates a fundamental change in direction and approach is absolutely necessary (Shahtahmasebi, 2013).

References

Antidepressant use in New Zealand doubles. (2012). The Government’s drug-buying agency, Pharmac, says it is monitoring the growing use of anti-depressants in New Zealand. http://www.radionz.co.nz/news/national/117826/pharmac-monitoring-use-of-anti-depressants.

Associate Minister for Health. (2006). The New Zealand Suicide Prevention Strategy 2006-2016. Wellington: Ministry of Health, http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-suicide-prevention-strategy-2006-2016, accessed 10 June 2019.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2004a). Suicides, Australia, 2010 (cat no. 3309.0). http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/ViewContent?readform&view=productsbytopic&Action=Expand&Num=5.7.14, accessed 17 May 2019.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2004b). Suicides: Recent Trends, Australia, 1993 to 2003 (cat no. 3309.0.55.001). http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/ViewContent?readform&view=productsbytopic&Action=Expand&Num=5.7.14, accessed 17 May 2019.

Hamdi, E., Price, S., Qassem, T., Amin, Y., & Jones, D. (2008). Suicides not in contact with mental health services: Risk indicators and determinants of referral. J Ment Health, 17(4), 398-409.

Hjelmeland, H., Dieserud, G., Dyregrov, K., Knizek, B. L., & Leenaars, A. A. (2012). Psychological Autopsy Studies as Diagnostic Tools: Are They Methodologically Flawed? Death Studies, 36(7), 605-626.

Jorm, A. (2018). Australia’s ‘Better Access’ scheme: Has it had an impact on population mental health? Aust NZ J Psychiatry, 52(11), 1057-1062.

Mental Health and Addiction Inquiry. (2018). He Ara Oranga : Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction. https://mentalhealth.inquiry.govt.nz/inquiry-report/.

Ministry of Health. (2006). New Zealand Suicide Trends: Mortality 1921-2003, hospitalisations for intentional self-harm 1978-2004. Wellington: Ministry of Health, New Zealand.

Ministry of Health. (2007). Patterns of Antidepressant Drug Prescribing and Intentional Self-harm Outcomes in New Zealand: An ecological study. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Ministry of Health. (2019). Every Life Matters – He Tapu te Oranga o ia tangata: Suicide Prevention Strategy 2019–2029 and Suicide Prevention Action Plan 2019–2024 for Aotearoa New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Pridmore, S. (2014). Why suicide eradication is hardly possible. Dynamics of Human Health (DHH), 1(4), http://journalofhealth.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2014/2012/DHH_Saxby_Eradicating-suicide.pdf.

Pridmore, S., & Rostami, R. (2020). Suicidal behaviour disorder: a bad idea. In S. Shahtahmasebi & H. Omar (Eds.), The Broader View of Suicide (pp. 265-279). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2003). Suicides by Mentally Ill People. ScientificWorldJournal, 3, 684-693.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2005). Suicides in New Zealand. ScientificWorldJournal, 5, 527-534.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2013). De-politicizing youth suicide prevention. Front. Pediatr, 1(8), http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fped.2013.00008/abstract. doi: 10.3389/fped.2013.00008

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2019). A “Wellbeing” approach: flawed politics or a gimmick? Dynamics of Human Health (DHH), 6(2), https://journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=1830.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2022). Editorial: mental health: it’s all relative. Dynamics of Human Health (DHH), 9(1), https:www.journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=2825.

Shahtahmasebi, S., & Shahtahmasebi, R. (2010). A Holistic View of Suicide: Social Change and Education and Training. Journal of Alternative Medicine Research, 2(1), 115-128.